MENTION sake to an Australian, and the response may provoke an involuntary shudder and grim memories of something warm they poured down their throat on the wrong side of midnight on a big night out. Or maybe they’ll recall something nondescript being decanted with little fanfare to accompany the sushi at their local Japanese restaurant.

An increasing number of Australians, however, are discovering the pleasures of drinking premium sake, at home or in the growing number of specialist sake bars that are popping up in our capital cities.

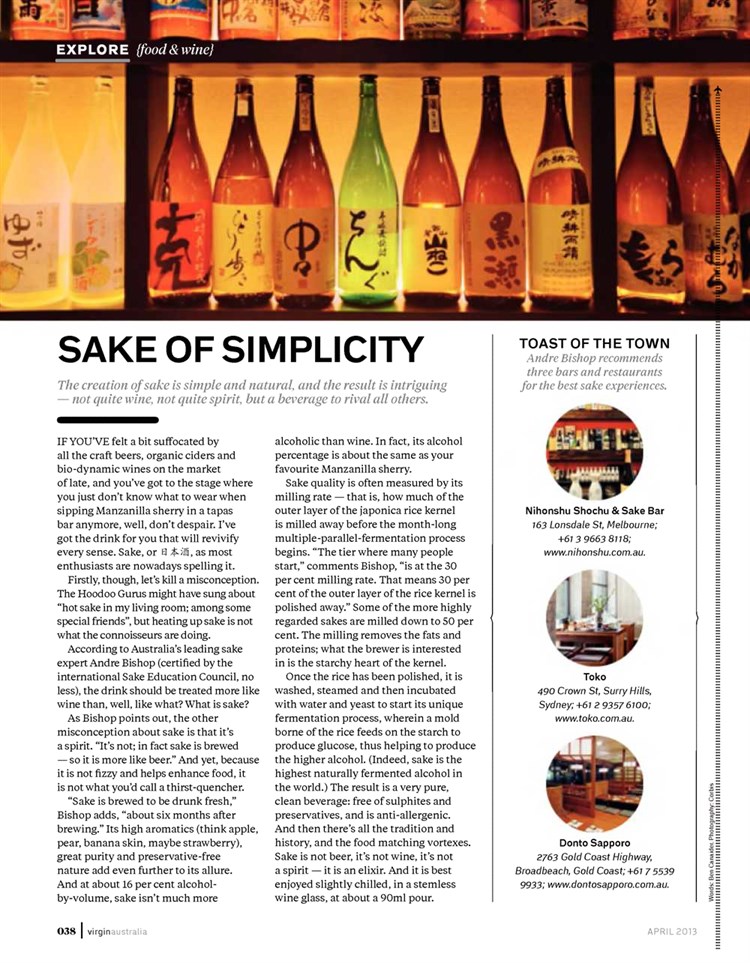

Melbourne-based restaurateur and bar owner Andre Bishop has made it his mission to elevate Japan’s most renowned drink to the status he says it deserves — something akin to that of wine. Since opening his first bar in 2000, Bishop has done perhaps more than any other Australian to raise the profile (and consumption) of Japanese sake in Australia.

“I grew up obsessed by manga and anime and went to Japan for the first time in 1996 to go backpacking,’’ Bishop says. “When I came back I thought: ‘How can I turn my passion and appreciation for this country into my livelihood?’

“So in 2000, I opened my first sake bar (Nihonshu, in Melbourne city). In the late 90s sake was really just in the realm of Japanese restaurants. I wanted to take it out of that and deliver it as a beverage that people could enjoy at a bar. My mantra was to get more Australians to drink more sake.”

In that task he has succeeded. Official figures show importation of sake has been growing at more than 10 per cent a year for most of the past five years.

“Through most of the noughties it was still a novelty,” Bishop says. “It was a slow progression, people were drinking it, but it’s really only been in the last four years that it has really gained groundswell. It has coincided with that interest in food and food culture … and just a growing awareness of craft and boutique produce.”

In my four-year stint as The Australian’s correspondent in Japan I sampled many different sakes, ranging from the very bottom (the One Cup Ozeki that’s available for less than $2 in vending machines) to top drops retailing for several hundred dollars a bottle.

I would usually choose a sake according to region, picking out prefectures such as Niigata that are famous for the quality of their rice, and occasionally choosing Fukushima sake in solidarity with the troubles the prefecture experienced after the nuclear accident.

But Bishop says styles don’t conform to regions and it’s better to work out your flavour preferences and match the sake to the occasion or the food you are eating. “There is such a broad range of flavours — sweet and dry, full bodied and light — the sake world is just as diverse as the wine world.”

Sake can be broadly divided into two types: junmai and honjozo. Junmai sake is made with rice, water and koji (the mould that sparks the fermentation process), whereas honjozo sakes have a small quantity of alcohol added. It’s not a case of one being superior to the other, they are different styles. A Japanese friend insists junmai sakes are kinder to your head if you drink too many, although I am not so sure.

The other main classification system is based on the level of polishing of the rice. Among the premium sakes, daiginjo sake has at least 50 per cent of each grain milled off, while ginjo has more than 40 per cent removed. Basic premium sake has at least 30 per cent of the outside of each grain removed. Below this, sake is usually designated futsu-sho, or everyday sake.

Bishop’s Nihonshu sake bar in Lonsdale Street is named after the drink’s name in Japan. Sake in Japanese is simply an alcoholic drink, whereas nihonshu translates as Japanese liquor.

Bishop has another restaurant, Kumo Izakaya, in East Brunswick, pairing sake with high-end izakaya (tapas) style food.

He and Japanese-born Sydney chef Tetsuya Wakuda are the only Australians to be qualified as sake masters and sit among a group of just 47 worldwide, most of whom are in the industry in Japan.

Over cups of sake at Nihonshu, Bishop tells me his sensei, or mentor, in the sake world was John Gauntner, an American who is perhaps the leading sake authority in the English-speaking world. The name rings a bell so I pull out my phone to discover he is on my contact list.

Just before I returned to Australia last year I went to a tasting of famous brewer Dassai’s premium sake. Gauntner was interpreting for the Dassai chairman’s speech and was so fluent I grabbed him afterwards, thinking he was purely an interpreter, to ask if he could interpret for an interview I was chasing with Japan’s PM, Shinzo Abe. Somewhat taken aback, he replied he was nowhere near up to the standard required, and he sounded word-perfect on this occasion only because the speech was about sake, his life’s passion.

As Bishop pours a glass of barrel-aged sake, or koshu, he explains that the labels, which are usually in Japanese, are one of the main barriers to acceptance among Australian drinkers. He has been advising brewers to keep the Japanese characters on the front label while translating their story on the back.

“It is something that I have been campaigning on and having some success with. Traditionally it is all in Japanese … we would like to see where it comes from, who the brewer was, what are their comments about this type of sake,’’ he says. “Thankfully, Japanese brewers are understanding that if they want to educate Western people about sake it is going to be advantageous for them to tell their story on the label.’

Going out for Sake

Sydney: Kuki Tanuki on Erskineville Road has an interesting range of sakes and is dedicated to explaining sake to Australian drinkers. It also offers a range of small bites, including sushi and sashimi. Fuku, on George St, has a nice range of sakes and some more elaborate food offerings. The menu also explains the origin and flavours of the sakes sold.

Melbourne: Nihonshu, in the CBD, shares premises with Izakaya Chuji, one of the oldest izakaya restaurants in Australia. It has a big range of sake and shochu, which can be drunk with food from Chuji. The drinks list gives full explanations of each sake and grades them on a graphic flavour scale. Kumo Izakaya in East Brunswick, Andre Bishop’s main restaurant, also has a long list of sakes and shochu, as well as Japanese craft beer, and serves high-end izakaya food. Akachochin, on the banks of the Yarra in Melbourne’s South Wharf, is another izakaya that takes its sake seriously with a great list of 40 sakes with food to match.

Perth: Fuku, in Perth’s Mosman Park, claims to have the largest range of sake in Western Australia with more than 500 varieties. Specialising in omakase teppanyaki (grilled dishes chosen by the chef and cooked in front of you), it’s receiving good reviews for its sake and Japanese food.

Brisbane: Trusted friends recommend Sake Restaurant and Bar, which now has branches in Sydney and Melbourne too. Located on the riverside Eagle St Pier in central Brisbane, it has quality Japanese food and a large range of sakes and shochu (distilled spirit) by the glass and bottle. The two branches of Sono Restaurant — Sono Portside in Hamilton and Sono Restaurant in the Queen St Mall — offer a good range of sake with brief explanations on the menu.

mountain range in Katano City.

mountain range in Katano City. << Photo: Current Director, Yasutaka Daimon

<< Photo: Current Director, Yasutaka Daimon

City, an area long referred to as “Nanbu no Kuni.” It is an area blessed with lush and beautiful natural reserves, fine water, two national parks, and a lake. We were established in 1902, but at first were only a sake retailer. In 1915 we acquired the necessary licenses and began to brew sake. Our facilities lie on what was once known as the Okumura Kaido, old National Route Number 4. The all-glass front of the main building gives the proper impression of a shop, while the kura (brewery building) behind it is a gorgeous, all-wood, traditional structure. Its ancient, thick pillars and their shining dark color convey the long history of the place.

City, an area long referred to as “Nanbu no Kuni.” It is an area blessed with lush and beautiful natural reserves, fine water, two national parks, and a lake. We were established in 1902, but at first were only a sake retailer. In 1915 we acquired the necessary licenses and began to brew sake. Our facilities lie on what was once known as the Okumura Kaido, old National Route Number 4. The all-glass front of the main building gives the proper impression of a shop, while the kura (brewery building) behind it is a gorgeous, all-wood, traditional structure. Its ancient, thick pillars and their shining dark color convey the long history of the place. plenty of off-flavors. Instead, we decided to brew “clean and beautiful” sake. Hence, we created the Nanbu Bijin brand name to personify our sake. Nanbu stands for the region, and Bijin (meaning beautiful woman) for the delicate, light, and clean nature of our sake. Our sake is brewed with medium-hard water that is purified naturally as it courses through the mountain rock on its way to the sea. We use Hito-mebore, Toyonishiki and Sasanishiki sake rice and of course, our sake is brewed by a Nanbu-area toji.

plenty of off-flavors. Instead, we decided to brew “clean and beautiful” sake. Hence, we created the Nanbu Bijin brand name to personify our sake. Nanbu stands for the region, and Bijin (meaning beautiful woman) for the delicate, light, and clean nature of our sake. Our sake is brewed with medium-hard water that is purified naturally as it courses through the mountain rock on its way to the sea. We use Hito-mebore, Toyonishiki and Sasanishiki sake rice and of course, our sake is brewed by a Nanbu-area toji. << Photo: Kuramoto Kuji Hideo and Son, Kuji Kosuke

<< Photo: Kuramoto Kuji Hideo and Son, Kuji Kosuke sake brewing. Check it out at

sake brewing. Check it out at  Our toji, Mr. Hajime Yamaguchi, is truly amazing. He has been with us since 1964, more than a quarter of a century. He has won countless awards from the tax department, as well as from the Nanbu toji association. In 1992, he was selected by the Ministry of Labor as one of the 100 Great Craftsmen. While fervently preserving traditions, he actively develops new technology and contributes much to the industry. Yet, he remains humble. “No matter how long I make sake, I am clueless about brewing. In the end, it is a matter of understanding the relationship between the water and the rice, and it is difficult to try and grasp the infinite variations between them.” Sake is born of the experience and efforts of the toji, and their love for the sake they brew. We are proud and privileged to have such a skilled and intuitive toji with us.

Our toji, Mr. Hajime Yamaguchi, is truly amazing. He has been with us since 1964, more than a quarter of a century. He has won countless awards from the tax department, as well as from the Nanbu toji association. In 1992, he was selected by the Ministry of Labor as one of the 100 Great Craftsmen. While fervently preserving traditions, he actively develops new technology and contributes much to the industry. Yet, he remains humble. “No matter how long I make sake, I am clueless about brewing. In the end, it is a matter of understanding the relationship between the water and the rice, and it is difficult to try and grasp the infinite variations between them.” Sake is born of the experience and efforts of the toji, and their love for the sake they brew. We are proud and privileged to have such a skilled and intuitive toji with us. Andre Bishop is a Melbourne based Sake Professional and is recognized as one of Australia’s leading authorities on Sake. His 12 years of experience in designing Asian and specifically Japanese venues include well know Melbourne establishments Robot Bar and Golden Monkey. He currently owns the 22 year old Japanese dining institution Izakaya Chuji and Sake Bar Nihonshu. He is also co-owner and founder of Melbourne’s flagship Izakaya and Sake Bar, Kumo in Brunswick East. Andre studied Sake in Japan and is the only Australian who currently holds a Level 2 Sake Professional Certificate from the International Sake Education Council.

Andre Bishop is a Melbourne based Sake Professional and is recognized as one of Australia’s leading authorities on Sake. His 12 years of experience in designing Asian and specifically Japanese venues include well know Melbourne establishments Robot Bar and Golden Monkey. He currently owns the 22 year old Japanese dining institution Izakaya Chuji and Sake Bar Nihonshu. He is also co-owner and founder of Melbourne’s flagship Izakaya and Sake Bar, Kumo in Brunswick East. Andre studied Sake in Japan and is the only Australian who currently holds a Level 2 Sake Professional Certificate from the International Sake Education Council.

Nanbu Bijin Brewery (formerly known as Kuji Shuzo) is located in northern Japan’s Ninohe City, an area long referred to as “Nanbu no Kuni.” It is an area blessed with lush and beautiful natural reserves, fine water, two national parks, and a lake. We were established in 1902, but at first were only a sake retailer. In 1915 we acquired the necessary licenses and began to brew sake. Our facilities lie on what was once known as the Okumura Kaido, old National Route Number 4. Theall-glass front of the main building gives the proper impression of a shop, while the kura (brewery building) behind it is a gorgeous, all-wood, traditional structure. Its ancient, thick pillars and their shining dark color convey the long history of the place.

Nanbu Bijin Brewery (formerly known as Kuji Shuzo) is located in northern Japan’s Ninohe City, an area long referred to as “Nanbu no Kuni.” It is an area blessed with lush and beautiful natural reserves, fine water, two national parks, and a lake. We were established in 1902, but at first were only a sake retailer. In 1915 we acquired the necessary licenses and began to brew sake. Our facilities lie on what was once known as the Okumura Kaido, old National Route Number 4. Theall-glass front of the main building gives the proper impression of a shop, while the kura (brewery building) behind it is a gorgeous, all-wood, traditional structure. Its ancient, thick pillars and their shining dark color convey the long history of the place. In 1951, we decided to stop making the sweet sake so common back then, a style with plenty of off-flavors. Instead, we decided to brew “clean and beautiful” sake. Hence, we created the Nanbu Bijin brand name to personify our sake. Nanbu stands for the region, and Bijin (meaning beautiful woman) for the delicate, light, and clean nature of our sake. Our sake is brewed with medium-hard water that is purified naturally as it courses through the mountain rock on its way to the sea. We use Hito-mebore, Toyonishiki and Sasanishiki sake rice (see Rice Varieties for more), and of course, our sake is brewed by a Nanbu-area toji.

In 1951, we decided to stop making the sweet sake so common back then, a style with plenty of off-flavors. Instead, we decided to brew “clean and beautiful” sake. Hence, we created the Nanbu Bijin brand name to personify our sake. Nanbu stands for the region, and Bijin (meaning beautiful woman) for the delicate, light, and clean nature of our sake. Our sake is brewed with medium-hard water that is purified naturally as it courses through the mountain rock on its way to the sea. We use Hito-mebore, Toyonishiki and Sasanishiki sake rice (see Rice Varieties for more), and of course, our sake is brewed by a Nanbu-area toji. sake brewing. Check it out at

sake brewing. Check it out at  Our toji, Mr. Hajime Yamaguchi, is truly amazing. He has been with us since 1964, more than a quarter of a century. He has won countless awards from the tax department, as well as from the Nanbu toji association. In 1992, he was selected by the Ministry of Labor as one of the 100 Great Craftsmen. While fervently preserving traditions, he actively develops new technology and contributes much to the industry. Yet, he remains humble. “No matter how long I make sake, I am clueless about brewing. In the end, it is a matter of understanding the relationship between the water and the rice, and it is difficult to try and grasp the infinite variations between them.” Sake is born of the experience and efforts of the toji, and their love for the sake they brew. We are proud and privileged to have such a skilled and intuitive toji with us.

Our toji, Mr. Hajime Yamaguchi, is truly amazing. He has been with us since 1964, more than a quarter of a century. He has won countless awards from the tax department, as well as from the Nanbu toji association. In 1992, he was selected by the Ministry of Labor as one of the 100 Great Craftsmen. While fervently preserving traditions, he actively develops new technology and contributes much to the industry. Yet, he remains humble. “No matter how long I make sake, I am clueless about brewing. In the end, it is a matter of understanding the relationship between the water and the rice, and it is difficult to try and grasp the infinite variations between them.” Sake is born of the experience and efforts of the toji, and their love for the sake they brew. We are proud and privileged to have such a skilled and intuitive toji with us.

Katano City (near Osaka).

Katano City (near Osaka). << Photo: Current Director, Yasutaka Daimon

<< Photo: Current Director, Yasutaka Daimon

♦ Kura History ♦

♦ Kura History ♦ ter from which it is brewed. Our water is extremely soft, but it ferments well at low temperatures. So we make our sake with long, low-temperature fermentation, which allows a gentle ginjo fragrance, and a fresh lively flavor to develop. Also, as we know koji is where good sake begins, we do it our own way, which is to make the koji at a slightly higher temperature than usual. This helps give our sake a clean and pleasant finish.

ter from which it is brewed. Our water is extremely soft, but it ferments well at low temperatures. So we make our sake with long, low-temperature fermentation, which allows a gentle ginjo fragrance, and a fresh lively flavor to develop. Also, as we know koji is where good sake begins, we do it our own way, which is to make the koji at a slightly higher temperature than usual. This helps give our sake a clean and pleasant finish. ♦ The People ♦

♦ The People ♦

Our current toji is Touda Masahiko. His many years of experience with us continue to allow us to provide consistently flavorful sake to our customers. In 1997, our former toji, Mr. Narikawa Mitsuo, retired from active toji work, but remains on with us as an advisor. He was replaced by Mr. Oka Kentaro, a wonderful Hiroshima toji who died in an unfortunate accident in 2004. Both were highly skilled and creative brewers, helping to make Suwa Izumi what it is today. Mr. Narikawa was the only Hiroshima toji in this region while he was active, as was Mr. Oka. In 1996, Narikawa won an award from the Ministry of Labor as being a “Famous Craftsman of this Generation.”

Our current toji is Touda Masahiko. His many years of experience with us continue to allow us to provide consistently flavorful sake to our customers. In 1997, our former toji, Mr. Narikawa Mitsuo, retired from active toji work, but remains on with us as an advisor. He was replaced by Mr. Oka Kentaro, a wonderful Hiroshima toji who died in an unfortunate accident in 2004. Both were highly skilled and creative brewers, helping to make Suwa Izumi what it is today. Mr. Narikawa was the only Hiroshima toji in this region while he was active, as was Mr. Oka. In 1996, Narikawa won an award from the Ministry of Labor as being a “Famous Craftsman of this Generation.”